What do you think you would catch if you threw a fishing line into the Plenty River at Yallambie? A Redfin perhaps? The “Salmon of Doubt”? An old boot?

I was walking in Yallambie Park the other day below Tarcoola Drive and heard movements on the river bank below me. A few Yallambie likely lads and their girlfriends were down by the riverside with fishing gear and lines trailing into the water. The esky they had brought along with them probably contained little in the way of a catch, but at a guess, lots in the way of lager, the obligatory essential for a good day’s fishing anywhere.

Although the sight of Yallambie anglers is about as uncommon these days as a monster in Loch Ness, a few die hard fishermen are still seen now and then elsewhere along the river. There were plenty of fish in the Plenty once upon a time, enough even for an angling club to form upstream from Yallambie at Greensborough in 1926.

Under the name of the “Greensborough Angling Club”, it met initially at the Greensborough Masonic Hall in Ester St before building premises on the west bank of the Plenty at 161 Para Rd, (then Rattray Rd). The club is still active today and is one of Victoria’s oldest angling clubs, although it’s doubtful whether they fish the River competitively at the back of the club house much anymore. Easier I would say to put in an order at the local fried fish and chip shop.

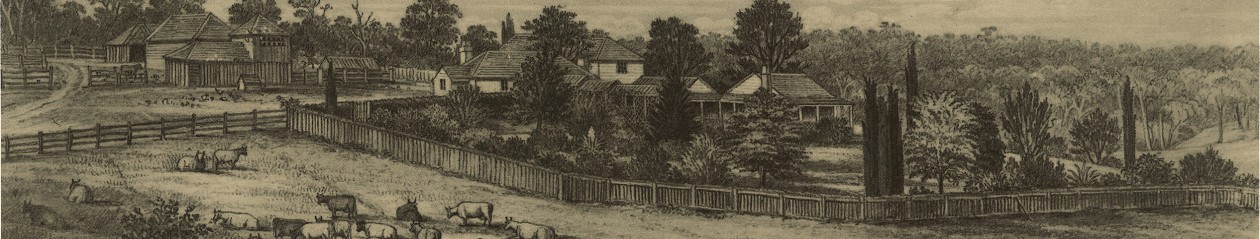

Frank Wright, a grandson of Thomas Wragge, the landholder of Yallambie in the second half of the 19th century, wrote of his earliest memories and of fishing on the Plenty River in a paper entitled “Recollections of the Plenty River”, extracts of which were quoted by Winty Calder in “Classing the Wool and Counting the Bales”.

The Plenty water, from my earliest days, was always said to be exceedingly pure, and in the 1920s I heard a professor of engineering say that Yan Yean water was so pure that, without treatment, it could be used indefinitely as boiler-feed water.

I have some slight recollections of the Plenty at Yallambie in the very early 1900s, but my main experiences there were during the years after 1910 when the unoccupied property became, to all intents and purposes, my happy hunting ground… we might walk from and return to Heidelberg for a day’s fishing, or go by train to Greensborough, walk and fish our way to Yallambie and then walk back to Heidelberg; or sometimes my father would pile three or four of us boys and our camping gear into the family buggy and leave us to our own devices on the banks of the river for a week or two at a time. The old (Yallambie) orchard provided us with fruit, the creek with fish, and we (learnt) to look after ourselves. Thus we got to know the river well, at least the length of it between Greensborough and the Lower Plenty Bridge.

It never occurred to us not to drink the water straight out of the river. It was crystal clear, an always flowing stream of pools and little rapids. Trees and bush lined its banks, and here and there an old fallen tree provided a bridge crossing. In other places crossings were easily made.

Possums and platypus were plentiful. Often we would see six or ten platypus in a day. We used to catch blackfish and mountain trout, and once we caught a rare native fish called a marbled trout. It was like a rather narrow 10-inch flathead in shape, with a mottled grey-black colouring. Eels and small freshwater lobsters also came our way.

Looking back, it is now realized, our hunting days at Yallambie bracketed the time that was the beginning of the end for these native fish. I don’t remember which we caught first, an English perch or a Murray cod; anyway, we caught both. Someone had put them in the Yarra and they had made their way up the Plenty, to add to our fun. But these two fish were, I believe, destroyers of the little blackfish and mountain trout.

My visits to the Plenty at Yallambie ceased with World War I.

Fishing has always been a hugely popular past time in Australia. My own father was a keen freshwater river fisherman in the years that followed that other World War. He and his old army mates, all ex POWs, kept a shack after 1945 on the Mitta Mitta River where they would disappear away from their families at irregular intervals to yarn about the “one that got away”. Some sort of wish granting, talking fish I have no doubt.

I remember going there years later as a child, around about the time that to quote my father, the building of the Dartmouth Dam “wrecked the Mitta for fly fishing”. There was a large drawing of a fish in outline on a wall of the shack which, as my father explained, was the outline of a trout which legend had it had been reeled in hook, line and sinker by my godfather, Uncle John. The men had traced the fish onto the wall to immortalize it before it went into the pan. “But take with a grain of salt, or at least a slice of lemon, that drawing and anything else your Uncle John tells you of his Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. Your Uncle John was a lousy fisherman. If you ask me, I reckon it was more like a fish finger.”

Like the later building of the Dartmouth, when a catching reservoir was built in the 1850s on the upper reaches of the Plenty River at Yan Yean, the river’s natural flow was forevermore diminished downstream. Mills closed for lack of water and farming practices had to be modified up and down the Plenty valley. The colonial government paid financial compensation to the mill owners whose business literally “dried up” overnight, causing some wags at the time to suggest that there was more money to made in building mills to claim the compensation than in actual mill operation. Oral history would suggest that in the early days of settlement a water driven, mill wheel was located at Yallambie. Indeed, Ethel Temby claimed to have seen the still visible foundations of this feature in the 1960s but locating the mill site within Yallambie Park today can only be described as a problematic exercise at best, although a cut through the river bank for watering cattle and old billabong depressions are still apparent.

Occasional floods on the Plenty River at Yallambie are still possible and at their highest point can cut right across the plain of the horseshoe bend in the vicinity of the billabong depressions.

A Wragge photograph from the 1890s shows the river in flood and in 1996, a century later, another flood was captured in this video clip:

There is no doubt that Yan Yean was a visionary engineering project for an infant colony when it opened in 1857. Certainly Yan Yean water was an improvement on the old system of collecting water from the Yarra, upstream from the settlement, and carting it around the town in barrels.

Visiting Australia in 1871, the English novelist Anthony Trollope, wrote of Melbourne’s water supply and stated, perhaps with some satire, that it “is supposed to be the most perfect water supply ever produced for the use of man. Ancient Rome and modern New York have been less blessed in this respect than is Melbourne with its Yan Yean. I do believe that the supply is almost as inexhaustible as it is described to be. But the method of bringing it into the city is not as yet by any means perfect… I will also add that the Yan Yean water is not pleasant to drink — a matter of comparatively small consideration in a town in which brandy is so plentiful.”

I’ve heard tell that ultra-pure water (literally H²O) produced for use in the medical industry, has the texture of water without the taste of water, and in fact it can be quite dangerous to drink in quantity. Sounds weird doesn’t it? Generally, it is the mineral content in water that gives water the taste we assume it doesn’t have. The use of lead piping in early Melbourne, used to deliver water around the city streets, was probably one reason for Trollope’s reservations about the quality. Consumers at the time were even advised to run their taps to waste for a few minutes each morning in an attempt to lessen the dangers associated with lead piping.

The “inexhaustible” supply described by Trollope all too soon also proved to be inadequate. Further diversions of streams into the Yan Yean system occurred and the 20th century saw the building of a series of new dams on many of the main rivers within casting distance of Melbourne. The last one was built on the Thomson River in west Gippsland within the memory of many people. When completed in 1983, the Thomson Reservoir was more than four times the capacity of Melbourne’s next largest reservoir and was supposed to drought proof Melbourne for all time. Like Yan Yean and the other reservoirs, it was never going to be enough of course. Australia is a dry country. So dry in fact that here in Victoria a few years ago, with the much vaunted Thomson standing almost empty, the politicians went all to water in the face of an ongoing drought and in a robbing “Peter to pay Paul” exercise, built a pipe line to bring water from the Goulburn Valley across the divide to Melbourne. And if that was not enough, at the same time they ordered the building of a massive desalination plant on the Bass Coast near Wonthaggi.

A desalination plant was always going to be a dumb idea and the fact that regular rainfall since its opening has saved the desalination plant (or the pipe line for that matter) from being used is scarcely the point. When you have to start manufacturing water it’s clear to me that you have a population that is living beyond the ecological limits of the environment.

As Melbourne continues to expand into an ever enlarging megatropolis, it is our environment that always pays the price. The latest “Sustainable Cities Index”, a study that rates 50 of the world’s most important cities from 31 countries, taking into account social, economic and environmental considerations, ranks Melbourne 17th in environmental considerations. The same study however ranks Melbourne fifth for profitability and 8th in social factors. I can see a trend developing, can’t you?

In “Classing the Wool and Counting the Bales”, Winty Calder further described some of the environmental stresses that beleaguered the Plenty River at Yallambie in the second half of the 20th century:

Bill Bush would remember platypus in the Plenty River during the 1950s, but both the river and its flood plain were degraded as residential development proceeded. Frank Wright continued returning to Yallambie until the 1970s, by which time his early memories of the property were in sharp contrast to current reality. It had become “a jumble of new roads and dwellings, and the formerly lovely Plenty River (was) a yellow mess of pollution and dumped rubbish.” (Letter from Frank Wright to Olive Shann.) He would never forget that:

“about 1970 or ’71, I… looked sadly at the once pure and beautiful Plenty. The water was a turbid orange colour from the stirred up clay. Raw bulldozed rubble edged the waterway in places. Tin cans, old tyres and other dumpers’ rubbish littered the scene. No sewerage drains served the many dwellings along the banks. I don’t want to see the Plenty again.” (Frank Wright, “Recollections of the Plenty River”).

Soon after Frank’s last visit to that river, the water quality testing programme of the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works confirmed his fears that the Plenty was so polluted it could no longer support aquatic life in its lower reaches. However, by then, a main sewer traversed the whole length of the river with branch sewers connected to it at various points.

Around the time Frank Wright wrote his epilogue of the Plenty River, a report from the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works put forward the notion that by 1990 the then polluted river systems of Melbourne would be mended. In fact it claimed that the Yarra, Melbourne’s perennial “upside down river”, would be flowing by then like some sort of Perrier at Dights Falls in Collingwood. Or words to that effect.

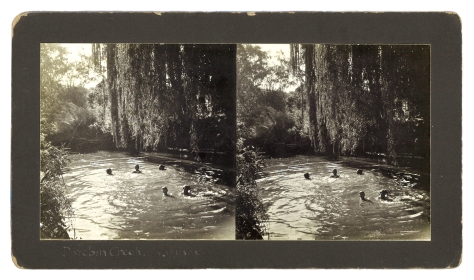

It seems hard to believe now, but the Yarra River and its tributaries at Heidelberg, the Plenty River and Darebin Creek all had their swimming holes at one time, some with suburban beaches and pools, dug out surrounds and semi concreted sides rather like sea baths — that was before river pollution made them unfit or at least unfashionable for use.

The remnants of a swimming pool on the Plenty River at Greensborough, a little upstream from Yallambie, are still visible and can be found just below the Main Road Bridge. The Greensborough pool was built as a “Susso” project in the Great Depression at a cost of £200 and was of cement and blue stone construction. It was opened in 1937 by the Mayor of Heidelberg, Councilor Robert Reid with demonstrations of swimming by leading swimmers of the day. It now makes a convenient platform for occasional anglers who would probably balk at the idea of getting their feet wet in the sometimes murky water.

A very good swimming beach of sand at Sills Bend in Heidelberg was still being risked by hardy souls when I was a boy but reduced and changing river flows have affected stream form and that beach consists now mainly of silt and clay when last I visited. I believe there was formerly a camping spot used by the Scouts located just down river from Sills Bend at Bulleen near what is believed to be today one of the most polluted ground locations in Heidelberg — namely the old gasometers site. Camping there was probably never a very good idea. Swimming in the Yarra these days is limited largely to around Warrandyte and to further upstream.

Against all odds and in the face of continued suburban expansion, by the 1990s Melbourne’s rivers were indeed considerably cleaner than from the time when Frank Wright wrote about the Plenty. Still not quite the promised Perrier but things had improved by 1997 to the extent that the local newspaper was able to report that platypus were once again occupying the Plenty River at Yallambie, in the vicinity of the Lower Plenty Rd Bridge. The following year a fishing event was organized for the river codenamed “Catch a Carp Day”. It was intended to reduce the numbers of these introduced European fish in the Plenty River, the correct assumption being that the species was in competition with the native aquatic wildlife.

In January this year it was reported that a 20 year old platypus was found in the Plenty River during a spring survey in 2014 and that, “a breeding population exists at least as far downstream as the mouth of the Plenty River, about 15 kilometres from downtown Melbourne”. (The iconic Platypus is a peculiar animal. A semiaquatic, egg laying, mammal it is the sole living representative of the family Ornithorhynchidae, in the genus Ornithorhynchus (literally bird billed). When stuffed examples were sent for study from Australia to Britain at the end of the 18th century, outraged scholars believed they were the victims of an attempted elaborate antipodean hoax. They infamously tried to remove the “stitching” on the platypus bill that they were sure had been employed in the forgery and the marks of the scissors can still be seen on the specimen on display today in the British Museum of Natural History.)

In the 19th century it was not unknown for platypus pelts and the furs of other rare native species to be turned into rugs and coats like some sort of Australian “One Hundred and One Dalmatians”. A pity nobody stripped their crinoline for PeTA in the 19th century. The Platypus is of course a protected species these days but it remains at risk from pollutants in rivers and the practice of illegal netting. A local newspaper story last month warned about illegal fishing practices and mentioned that two platypuses had recently been found dead in the Yarra River near Laughing Waters Rd, Eltham.

March 1st, is designated “Clean Up Australia Day” 2015, a day when many socially conscious Australians are getting out into the community to clean up the environment. There is a group meeting today in Yallambie Park where no doubt much good work will be done along the environs of the Plenty River, clearing the rubbish washed into the river by overnight rain. “Clean Up Australia Day” is a great Australian idea, the concept of which has spread to nations all around the world, but it is just one day of the 365¼ days in a year.

People love water features near their homes, be they bayside, a natural stream running through parkland, or artificial lakes in the manner of Yallambie’s, “Cascades” and “Streeton Views” housing estates. However, while storm water continues to empty into the suburban river system, every poisonous cigarette butt dropped from a car window, every oil spill that goes onto the road and the proceeds of every one of man’s best friends who ever uses a Ned Flander’s nature strip as a make shift dunny, all of it eventually ends up in one of our rivers or lake features. From there it makes its inexorable way to the Bay and thence to the oceans. After the oceans though there’s no where else to go on this “Pale Blue Dot”. That is the “Wall-e” reality of our world.

Fantastic Blog! I’ve read quite a few pages. I love way you’ve woven factual information with personal humor without losing any of the historical significance of the stories. Thanks for sharing this brilliant overview of a very special place. I am interested in researching upstream of Yallambie in the area from Partington’s Flat to Janefield and the Blue lakes.

Look forward to reading more on this great blog.

LikeLike

News to me . I thought they were something to do with fishing I haven’t been there for 30 years. I remember as a kid in the mid to late 80s goofing around in the overflow pipe that connects the kalparrin lake to the river under Yando st. We thought we were so cool. Would never have thought of swimming in the river. It’s logical to think that ‘in the day ‘ families wouldn’t have given it a second thought.

I guess growing up when I did as a city boy river activity was restricted to throwing/skimming rocks into or across it.

LikeLike

We use to swim in the Yarra as kids. Occasionally I still pull on the togs at Warrandyte if it’s hot enough, but you would never think of putting your head into the water. I remember once upon a time putting air mattresses into the Yarra at Templestowe with my mates and sailing down river all the way to Heidelberg. That was when we were young and foolish. Got fabulously sunburnt for the effort.

LikeLike

Thanks for this great commentary. My brother brought a platypus home from the Plenty at the bottom of Yallambie Road in the late 1950s. Our parents phoned the zoo to come and collect it – why didn’t they get him to take it from whence it had come, I now wonder…..

LikeLike