The green, bug-eyed monster from outer space is an image familiar to most people. It draws its inspiration from the pulp novels and B grade movies of the 1950s when the bug eyed monster standing on the gang plank of his flying saucer, armed with a death ray and demanding to be taken to a leader was a metaphorical vision for the collective fears of a post-World War 2, post-Colonial world dominated by Cold War. Leaders might be in short supply these days and a new hot war has replaced the Cold but you can bet your bottom dollar the bug eyed monsters are still out there, waiting to do their darndest as the world goes down a familiar path.

With hundreds of billions of stars in this galaxy and billions of galaxies in an ever expanding universe beyond you would think there would be plenty of room for the bug-eyed in us and everything else besides. Since about 1960 though, various SETI experiments around the world have been scanning the heavens for extra-terrestrial intelligence and have found guess what? Nothing – which raises a question first posed by Enrico Fermi in 1950, the so called “Fermi Paradox”. If alien life is waiting for us somewhere out there, with the universe the size it is, well, where is everybody? Frank Drake attempted to quantify this question with his famous equation in 1961, but as the equation must by need use purely conjectural starting data, the answer to Drake is always going to be entirely arbitrary with a solution anywhere from the number one, (that’s us), to just about any other number you care to want to believe in.

In fiction, Douglas Adams thought of a widely populated galaxy where interstellar travel was such a commonplace that hitching a ride on a passing space ship wasn’t such a big deal. His explanation for UFO sightings was simplicity itself. UFO’s were “rich kids with nothing to do”, he said. Cruising around in their space ships on the lookout for planets that hadn’t made interstellar contact, they would find an isolated spot and find some poor geek whom no one’s ever going to believe and strut about in front of him wearing silly antennas on their head making beep, beep noises.

Adams’ aliens it seems had a penchant for the childish, practical joke.

The late Stephen Hawking by contrast proposed a very different idea for the extra-terrestrial. Should our species ever make contact with aliens, Hawking thought the exchange would be brief. Very brief.

“If aliens visit us, the outcome would be much as when Columbus landed in America, which didn’t turn out well for the Native Americans.”

Forget the antennas and beep beep noises. The way Hawking saw it, the gulf would be so wide that the human race could be snuffed out of existence by the visiting extra-terrestrials before they even noticed us flattened underfoot.

Both theories have merit but when you think about it, they are like two sides of the one coin in where they will take us. Without proof it’s only ever going to be conjecture but in our search for the alien, do we really need to look so far afield? Look around on any given day and you will see what I mean. It’s all around us and it’s called life on this planet, in all its diversity.

I’m talking about the sort of alien life most of us hardly notice. There was such an alien in our garden only the other day, a strange, green bug-eyed creature. The praying mantis, to my mind is as near to a bug-eyed monster as you’re going to get on this planet. I certainly wouldn’t want to meet one up close if the scales were reversed.

The praying mantis is so named for the peculiar, “praying” stance it adopts with its forward limbs when hunting. After watching it for a while I began to get the distinct impression that maybe it wasn’t me who was doing the watching after all but that it was I who was being watched by those large, inquisitive eyes. What was it thinking in that tiny bug brain? Strange to relate, scientists have lately begun to accept that certain insects can experience a range of emotions and this one appeared to react to my presence, actively moving towards me when I motioned at it and standing quite happily on the back of my hand all the time while I studied it. The mantis is the bug most commonly used by people as a pet and they can live for about a year if looked after properly. At this time of year in the autumn the mantis female lays its eggs in a mating ritual that often involves the female eating the male, so you wouldn’t want to invite one home to dinner after meeting on Tinder.

In the Egyptian book of the dead the mantis aided in guiding souls to the underworld, and mantises form a common motif in the art of Pre-Columbian Nicaragua where they represent a spirit called Madre Culebra. Perhaps the best tradition though comes from South Africa where it’s said the appearance of a mantis in the home means your ancestors are present.

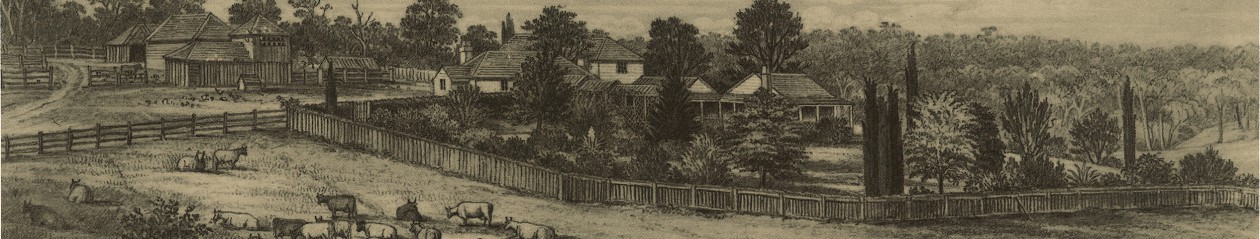

The green bug eyed monster in Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy tells Arthur Dent, “Hi fellas, hop right in, I can take you as far as the Basington roundabout?” commencing a wild ride for the pyjama wearing Arthur across the galaxy in a search for the question to the answer of the meaning of life, but maybe the story was missing the point all along. Our green friend was returned to the garden and is probably out there somewhere right now making plans for its next dinner date which is all part of an infinite universe only one part of which we ever get to experience on a regular basis. There is only one planet in the Universe where we can be for sure life exists and it is this one, right here, right now. We don’t need to hitchhike across the Galaxy to find it. If you go with the number one as your answer to Drake’s equation, then life on that one planet is an incomprehensibly precious thing, to be cherished in all its diversity, from the highest mountains to the deepest oceans, even to the occasional green, bug-eyed monster found on a leaf in Yallambie.