Some people kill it. Others put a stitch in it. But for most of us, there never seems to be quite enough of it.

Given the inscrutable nature of that thing we call time, it seems little wonder that the devices we use to mark it are made in the way they are. We say there are 24 hours in a day, but we only mark 12 of them on a typical analogue clock face, and we start the count not at zero, but at 12. Most of us can calculate at least to 10 in old Roman numerals, but it looks like horologists at some earlier point had other ideas. Have you ever noticed that the number four spelled out as Roman numerals on a vintage clock face is almost always recorded as four capital “I”s, or I,I,I,I, and not the letters “IV”? Early clock makers supposedly believed the face looked more symmetrical this way, but that doesn’t necessarily make it right.

It seems on the face of it that the very first mechanical clocks came without faces. They chimed on the hour to keep something vaguely resembling time and were accurate only to within 20 minutes or so of the day. This didn’t matter much as time was relative just to place, and not space as it is now. All that was needed back then was a count that kept time to some sort of local standard. It wasn’t until the end of the 14th Century that somebody had the bright idea of adding numbers to a rotating dial, with rotating hands on a fixed dial only coming later.

In the early colonial era of Melbourne, local time was set by lowering a ball at 1pm from a tower at Williamstown and another at Flagstaff Hill. These “time balls” were watched by shipping in the Bay and used by captains to set on board ships’ chronometers, which were of course vital in calculating correct longitude. By the 1860s the task of time keeping had been taken up by the Observatory in the Melbourne Botanic Gardens where time was checked by a nightly calibration of the stars and set on a Frodsham scientific regulator. An accurate time reading would be telegraphed to the Town clock the next morning from which people would check their own time pieces. These days in a world gone full circle, we’re more likely to check a public clock against the mobile device in our pocket than the other way round.

Up until the 19th Century, the most common way of keeping time anywhere in the world was with a sundial. At Jantar Mantar, Jaipur in India an enormous stone sundial was built in the 18th Century capable of measuring time to an accuracy of just two seconds. Most other sundials were accurate to within only half an hour and, it must be said, there was always the small matter about what to do when the sun went behind the clouds or at night.

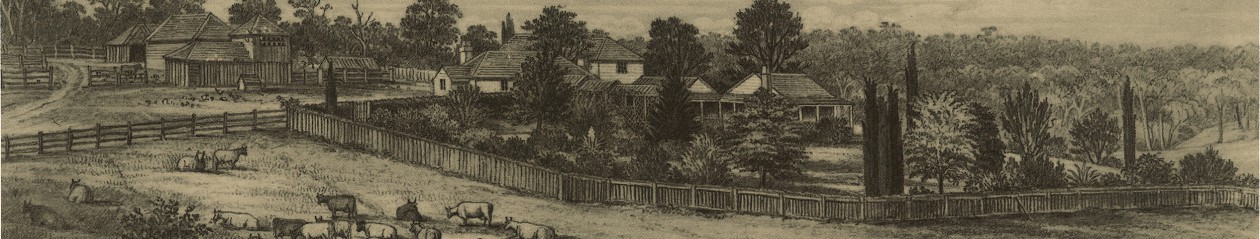

At Yallambie a sundial was present from the earliest days but whether this was for measuring time or simply as a garden aesthetic is debatable. Ethel Temby in her memoir recorded that it was located next to the old Bakewell oak at the south-west corner of the house. The sundial she said was firmly fixed to a large tree stump, the stump painted white and sitting in the shade of the massive Bakewell oak. It would seem reasonable to assume therefore that the dial was put in place at a time when the oak was still a relatively young tree and before the shade from its branches might be in the way of the dial’s performance. Ethel speculated that the stump had been there for as long as the Bakewell oak and lamented the fact that by the time the Temby family took possession of the property, the dial had been removed.

“A huge oak tree was probably an early planting by the Bakewells. The tree (from an acorn they brought?) is near the south-west corner of the present house. Perhaps as old as the tree – about 140 years – is the stump with remnants of white paint on it now almost completely in its shade. When the Tembys bought the house from A. V. Jennings the stump supported a sun-dial.” (Ethel Temby, writing in about 1980)

The fact that sundial technology had been developed in the northern hemisphere has resulted in our present understanding of what it means to do something in a “clockwise” direction. The word “clockwise” refers to the path the shadow of the sun follows around a sun dial in the north, so if sundials had been invented first in the Southern Hemisphere, “clockwise” would have been reversed. Therefore, if the Bakewells had brought a sundial with them from England, I’m afraid they might have found Yallambie time here going from back to front. Hmmm, this might explain a lot.

The divisions on a sundial, and by association a clock face, are based on the ancient Babylonian sexagesimal system of counting. You see, the Babylonians didn’t use fractions and 60 and its multiples are evenly divisible by 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 12, 15, 20 and 30. They also gave a circle 360° after noticing that there were a little over 360 days in a year.

Standard time zones were introduced into Australia in the 1890s when all of the Australian colonies adopted them. Before then, each city or town was free to determine its own local time, which was referred to as the Local Mean Time. It was the coming of the railways that demanded a universal standard, although there were arguments about what would constitute that standard. The debate was a bit like the argument over the numerous standards of railway gauge used in the Australian colonies, an argument which has never really been properly resolved. These days we have Australian Eastern Standard Time, Australian Central Standard Time and Australian Western Standard Time. We also have other time zones for Lord Howe and Christmas Islands, and separate daylight-saving adjustments in the summer across the States, just to confuse things still further.

Modern, quartz time pieces are accurate to within a few seconds of the year and Atomic clocks, which use quartz to measure the frequency of atoms, achieve an accuracy of seconds within millions of years. These are accuracies which I freely admit are not so much use to me. As mentioned in a previous post, time is kept in our kitchen by an old cuckoo clock whose occasional lunatic tune seems to me to sum up the story of our lives. Similarly, when I wear a watch I choose a vintage mechanical thing which is accurate enough for the way I tend to organize my day, if you know what I mean.

I have a couple of clockwork watches. One belonged to my wife’s grandfather. It was old fashioned when he wore it and he’s been dead 30 years. The other is even older and it has an intriguing story. You see, years ago my then girlfriend, later wife, gave me a travelling toilet kit that she had picked up in a junk shop for just a few dollars. She gave it to me because it was old fashioned, and I’ve always liked old fashioned things, and because it had been engraved at some time in the dim, dark ages past through some sort of chance coincidence, with my initials – I. McL.

These are the sorts of kit bags which were made once upon a time to contain toiletries in separate chrome topped containers for soap, toothbrush, and comb. These days you sometimes see the containers sold individually as collectables in vintage shops. Well, inside the toothbrush container, along with a decrepit toothbrush, I found somebody had hidden at a time in the past a gold, Deco era wristwatch. The crystal cover of the dial had been smashed and the movement was all rusted so I guessed the watch had gone into the pot a long time ago to hide the evidence of an accident.

This is a sort of thing to which I can relate. I appreciate the mechanical nature of old watches and the hands on skills that went into making them, but mostly I love speculating about the origins of this particular story.

“Has anyone seen my watch?” asks Dad.

“No,” said with a straight face, hands held behind back while putting something out of sight into a small bag. “I’m sure you’ll find it around here though, one of these days, if you look long and hard enough. Mind that little bit of broken glass there, won’t you?”

Good luck to you, Dad. You’re surely dust now which is where time is leading us all eventually. I guess you never did find your watch and I don’t suppose that anyone ever ‘fessed up. Funny that we shared the same, Roman numeral like initials, with lives separated today by almost a century of time. Call it synchronicity if you like, Carl Jung’s idea that events sometimes appear related even when they have no apparent connection at all.

There is a thing about time which extends beyond just the mechanical recording device on a dial placed out in the sun, the clock looking down at me from the wall or even that old thing buckled onto my wrist. These are all just the counters we have invented to mark the passage of time. They are not time itself. But I wonder, if there were no clocks, no people, indeed nothing in the universe and nothing to mark the passage of time, would there still be time?

It’s an age-old conundrum which launches into a philosophical realm. “If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?” The answer, at least according to an old way of thinking, is yes, the tree did make a sound because God alone heard it. The modern way of thinking about this though is that the temporal dimension we call time never really existed until space and time came together in some sort of Big Bang. More recently however, others have suggested that it was hanging around even before there was anything to bang on about. The people who use maths to argue about such things say there are Tachyons and rabbit holes with no return, and multiple dimensions and multiple universes beyond that. Then they start talking about Quantum superpositions and a cat left in a box that is both alive and dead and the whole thing gets a bit out of the question.

Our memories might seem to travel in a line from the past to the present and not beyond, but in Block Universe Theory the past, present and future are equally real. Or unreal? As one famous thinker put it, rather sensibly, “The past, present and future are only illusions, even if stubborn ones.” What I remember is not necessarily what you remember and what I remember isn’t necessarily what happened, anyway. A white rabbit in a waist coat rushing about, checking his pocket watch and exclaiming, “I’m late, for a very important date!” A Victorian school girl in white Edwardian dress running through the Australian bush screaming, “Miranda!” The timeless afternoons of childhood where time just stands still and pictures taken with an old plastic Instamatic. Fact or fiction? Past, present and future. Simulation or illusion? It’s time.

One thought on “It’s time”