The end of Jacobite ambitions on the bloody battlefield of Culloden’s Drummossie Moor on a cold, windswept April morning in 1746 was not the end of the story for its principal protagonist. While the Government would have preferred the end to feature the end of a rope, Prince Charles Edward Stuart, “The Young Chevalier” and rightful heir to the thrones of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, spent much of the following five months on the run from Government forces.

Sheltering in the heather, escaping from one scrape or near miss to another, the story of the flight of Bonnie Prince Charlie entered the folklore of legend. Long after the events of 1745 and 1746, the story of his failed uprising was told and toasted by the fireside in Scottish bothies and Baronial houses in both word and song:

…Speed bonnie boat like a bird on the wing,

Onward, the sailors cry.

Carry the lad that’s born to be king

Over the sea to Skye.

Though the waves leap, soft shall ye sleep,

Ocean’s a royal bed.

Rock’d in the deep, Flora will keep

Watch o’er your weary head…

Contrary to the popular idea of the Skye Boat Song lyric, it was Charles and not his companion Flora MacDonald who kept watch that night while the other slept on the trip from Uist in the Outer Hebrides to Skye off the west coast of Scotland, but the underlying sentiment remains the same. Dressed as he was as Flora’s maid servant, the boat party were almost certainly all aware of the true identity of their 5 foot 10 inch, cross dressing Royal passenger with the £30,000 Government bounty on his head, but it is part of the romance of the Jacobite legend that not one of them that night or those he encountered in the time before or after ever attempted to claim that reward.

Sadly though, when it was all over and Charles was safely back in France reviewing his shattered dreams through the end of a bottle, it was Flora and the broken regiments of the Jacobite Army who were left to bear the full force of Hanovarian retribution in the Highlands. For Flora herself this meant arrest and a short time spent as an unwilling guest at the Tower of London.

Altogether Flora MacDonald spent a year in a sort of loose captivity in and around London before being pardoned in the general amnesty of July, 1747 but in the intervening time, something else had happened. With the Jacobite threat now seemingly extinguished once and for all, there was time at last to sit back and take stock. The modest Highland lass who had bravely sheltered the arch rebel himself in his time of greatest need had somehow become a celebrity.

Flora was the toast of Society. Her portrait was painted by Ramsay in a boon to shortbread makers ever since. Sympathisers came to visit including Frederick, the non-pretending Prince of Wales who met her, partly to annoy his father, but principally to thumb his nose at his younger brother, the Duke of Cumberland, the “Butcher” of Highland infamy. The story goes that when Frederick asked Flora sternly why she had sided with his father’s enemies, she replied she would have done the same for anyone, even Frederick himself if she found him in similar distress. The answer is said to have impressed the heir apparent.

Following her pardon, Flora married and left Scotland for the American colonies where her husband ironically fought for the Hanovarian King against the Revolutionary armies. Forced by the British defeat in America to return to Scotland, Flora MacDonald died on the Isle of Skye in 1790 where Dr Johnson’s epitaph for her perhaps formed a lasting memorial for her life.

“Her name will be mentioned in history, and if courage and fidelity be virtues, mentioned with honour.”

The Highlands emptied of their people and the world moved on, but the memory of the Prince and his father, the “King Over the Water”, lingered on in memory. The romanticisation of the Jacobite story started during Flora’s life time but gathered pace in the 19th century, with George IV’s visit to Scotland in 1822 and Victoria and Albert’s 20 years later. Victoria and Albert’s visit began for them a long love affair with the country and with the Queen’s own somewhat dubious claim to a Scottish heritage. With this in mind then, it’s no wonder then that the large Scottish contingent present in Port Phillip’s pioneer settler society of the early 1840s had its own fair share of sentimentalist Scotophiles.

Arriving in the vicinity of the Plenty River in July, 1840 one of these settlers, John MacDonald of Skye and his wife Catherine established a farm of just under 200 acres which, perhaps not surprisingly given their heritage, they named “Floraville”. The land was part of Wood’s Portion 27 in the parish of Keelbundora north-west from Yallambie in Portion 8 and was purchased for £400. MacDonald paid for the land almost entirely with a mortgage from a cashed up Dr Godfrey Howitt who had arrived in the Port Phillip District just three months earlier with his wife and brothers in law, John and Robert Bakewell.

According to research made by a descendant, Betty Wooley, John MacDonald, ex Sergeant of the 26th Regiment, was born in Skye in 1806. He married Catherine in 1827 and came to Port Phillip in 1838. The land he purchased in Portion 27 backed onto the Darebin Creek but Betty believes that the MacDonald farm also had access to the Plenty River where it runs through the Plenty Gorge near present day Janefield.

A listing in Billis & Kenyon’s 1932 ”Pastoral Pioneers of Port Phillip” confusingly mentions a John Macdonald of “Floraville”, Lower Plenty, 1841 to 1842 and this may be the start of a certain uncertainty that has surrounded this story from the start. A contemporaneous newspaper article from the same time in “The Australasian” also suggests that: “In partnership with John W Shaw the Bakewells took out a depasturing licence in 1841 for a run called Floraville…” (The Australasian, October, 1936)

What does this mean? The Bakewells’ property “Yallambee” has at times been referred to in print as “Floraville”, a name which seemed to suit its garden perfectly. To get to the truth it is probably important to look at what happened to John MacDonald’s farming interests during the economic crisis that hit Port Phillip in the early 1840s.

With the onset of the recession the MacDonalds like so many other colonists, found themselves in financial difficulty. In February 1842 the family’s wet nurse sued for payment of unpaid wages and in April, labourers were reported to have taken MacDonald to court over an outstanding payment for the sinking of a well at Floraville.

Three months later Godfrey Howitt foreclosed on his mortgage to John MacDonald and the property was advertised for sale in the newspapers in terms that might well have been used to describe the Bakewells’ own Yallambee Park instead.

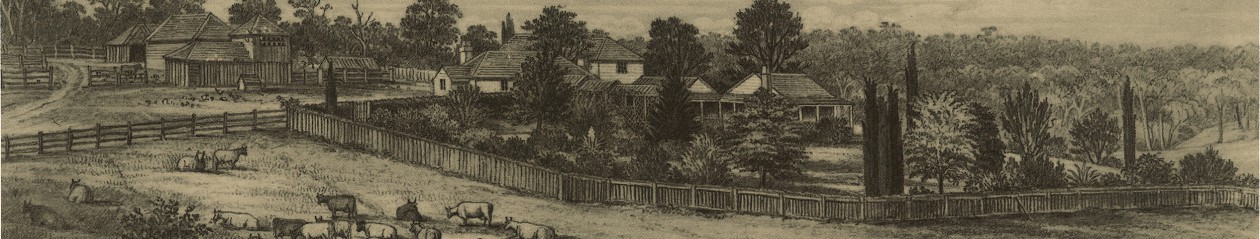

9th July 1842 – ‘Floraville Estate’, on the Plenty Road, the whole farm fenced in and subdivided into two paddocks of about one hundred acres each, there is about fifty acres under cultivation, or ready for the plough. On it is erected an excellent weather boarded house, containing six rooms and out offices, with barn and huts, stockyards etc., a well ninety feet deep of good never failing water. The view of the house is extensive; the roads are good, and the distance from town so short, that produce may be conveyed to the market at very trifling expense.

Even with the economic hardships of that time, Dr Godfrey didn’t have to look very far to find a ready buyer for the MacDonald Farm. On the 31st August, 1842 under the terms of the earlier mortgage, “Floraville Estate” was conveyed to Dr Godfrey’s brothers in law, John and Robert Bakewell for £575.

Perhaps this then is the origins of the name “Floraville” at Yallambee. The Bakewells may have used their newly purchased property further up the Plenty initially as a depasturing run as has been suggested in the Australasian article, but seven months later it is clear they were prepared to make it available for lease. In March 1843 the following advertisement appeared:

To Be Let, the Capital Compact Farm, Floraville, lately in the occupation of Mr Macdonald, only 11 miles from Melbourne, consisting of 200 acres of excellent land, The greater part clear, and first rate soil. Thirty acres are now in crop, and speak for themselves. The house is furnished with a veranda, and contains six rooms. The huts and stockyards are all superior. The proprietors being desirous of procuring a good tenant, intend to let the whole at an exceedingly low rent. For further particulars apply to Messrs J. and R. Bakewell the proprietors, Plenty Bridge.

After letting MacDonald’s Floraville before presumably selling it, did the Bakewells subsequently adopt the name as a sometime alternative to their Lower Plenty property, Yallambee simply because they liked the sound of it? They might not have fully appreciated the Jacobite implications of the name but it sort of fitted in with what Robert was trying to do with the garden at Yallambee at this time. Certainly it is from this point on that the name “Floraville” like the earlier title, “The Station Plenty”, is mentioned occasionally in the sources in context of the Bakewells’ Yallambee Park narrative.

Much has been made of the cultural history of the Plenty River and its course through the Upper Plenty Valley. Melbourne Water, as custodians of a part of that history as it applies to the Yan Yean catchment, and Whittlesea Council, with its reserve of heritage assets, do a very good job at defending that history, but lower down the picture has not always been so clear.

The Plenty River above and below the Plenty Gorge is like a tale of two rivers defined by the spill over of geology from the volcanic plains to the west. As Winty Calder explained in “Classing the Wool and Counting the Bales”, the two halves of the River mark the crossing point of two geologies, one ancient the other recent, at least in geological terms. The resulting landscape shaped the people and the lives of the settlers who came to stay.

“More than one million years earlier, basalt flows from the west had pushed the pre-existing Plenty River eastward before cooling and forming rock, the surface of which ultimately weathered into rich soil. The displaced river gradually cut down through the basalt and into the underlying, much older sandstones and mudstones…”

(Calder: Classing the Wool and Counting the Bales)

From its source on the forested slopes of Mt Disappointment, through the Yan Yean swamps and its final confluence with the Yarra River, the Plenty River is a rich cultural asset filled with interesting stories and history. The story of how Old MacDonald’s Farm became at some point and in some quarters, interchanged and intertwined with the Bakewells’ Yallambee Park, at least in name but perhaps also in memory, is but one of these.

So with this in mind, the next time you find yourself reaching across the table for that last piece of shortbread from a souvenir tin, if your eyes should meet a Jacobite biscuit heroine gazing your way, spare a thought for her eponym “Floraville”, another fragment of the Yallambie puzzle.

So with this in mind, the next time you find yourself reaching across the table for that last piece of shortbread from a souvenir tin, if your eyes should meet a Jacobite biscuit heroine gazing your way, spare a thought for her eponym “Floraville”, another fragment of the Yallambie puzzle.