Every Australian knows the story of the jolly swagman who liked to camp by a billabong while stuffing jumbucks into his tucker bag. In the song, the swaggie was brewing himself a billy tea “as he watched and waited ’til his billy boiled”, but somebody should have told him that a watched pot never boils. He was rudely interrupted from his repast by the arrival of a squatter on a gee gee, demanding an official look inside his bag.

It’s a well-loved tune, but I wonder.

If the swaggie had sat down for a cuppa with the troopers one, two and three instead of jumping into the billabong, would things have ended up differently that day? Tea has a way of diffusing a situation, calming nerves while invigorating debate, even something as problematic as the finer points of jumbuck ownership.

Tea has long been an integral part of the national character of this country. The obligatory meal of tea and damper was for years a staple of bush life and it was said that a bloke could survive on little else if need be. One of my earliest memories is of watching my dad, an old country boy, throw a handful of tea leaves into a boiling billy over a camp fire and watching him spin it by the handle over his head to draw out the brew. I always wondered how he got the boiling water to stay inside the pot.

Tea was right there at the start of Australia since it was a British tax on the stuff in the American colonies that led to the need for a new home for Britain’s convict classes after that party in Boston. The home eventually chosen would be New South Wales but there was a certain amount of wishful thinking that went into the planning stage of the new colony. Joseph Banks’ glowing report of the suitability of Botany Bay had been written with the rose coloured glasses of hindsight and the remembered heady days of his youth spent nearly two decades earlier in the company of the great explorer, James Cook at the other end of the world. Cook was by then a cannibal’s tooth pickings so when Botany Bay proved shallow and unsuitable for settlement, it was only with dumb luck that the First Fleet found one of the world’s great natural deep water harbours at Sydney, just to the north. Governor Arthur Phillip had high hopes for the new colony and his plans were for an ethnically harmonious, egalitarian and in particular alcohol free society, but it was a plan that would come massively unstuck in the face of the self-serving antics of the New South Wales Corps, the Rum Corps, a little later. It resulted in Australia’s only ever military coup d’état but one is left to wonder whether Australian history would have been any different if the 102nd Regiment of Foot had traded tea instead of rum?

Phillip packed a teapot in 1788 and served tea to his officers at regular afternoon tête-à-têtes at the leaking, canvas framed, First Government House he called home where the guests of honour would sometimes be Indigenous visitors who had been kidnapped especially for the occasion. You might call this an early attempt at Reconciliation, 18th Century style, but with the colony on the verge of starvation in those early years, maybe tea was used to hide the meagre sandwich board and take the edge off hungry appetites all round.

Unlike Phillip’s unwilling Indigenous luncheon companions, the convicts didn’t usually get invited to Phillip’s tea parties so the prisoners started to brew a native creeper, sweet sarsaparilla into a drink of their own, an approximation of tea which had the added advantage of some beneficial active antioxidants. For throats parched by the warm New South Wales climate though, it just wasn’t the same. In 1819, China tea was placed on the official convict ration and from that time onward it became an Australian staple. Many of the early colonists were soon growing and clipping their own tea bushes, but for years tea farming in Australia remained a relatively rare industry in spite of the Australian Town and Country Journal observing in 1881: “The plant might be grown in every garden in the colony where the climate is not colder than will suit the orange tree… The plant is hardy at Melbourne and Hobart, as well as Sydney.”

Tea drinking was assimilated into the habits of society and permeated both the public and private realm, becoming embedded in the very fabric of the Australian way of life along the way. Tea was used as a measure of civilisation in what was otherwise a sometimes primitive world. Describing a meeting place of Society in early Melbourne town, Northumberland Cottage, Georgiana McCrae wrote in her journal: “I was told that, in earlier days, the whole population of the settlement, about fifteen persons, had assembled (at Northumberland) to drink tea.”

And in a further commentary on combining the roles of wife and mother with Society hostess:

“Captain Cole, to tea, and whether for the sake of prolonging his stay beside his lady-love, or from actual thirst, he took no less than NINE of our small teacups full of tea. While pouring out the seventh cup I could hardly conceal the effects of a twinge of pain, but the captain and Thomas Anne didn’t make a move till 10pm.” (Georgiana’s Journal, Melbourne 1841-65)

After her visitors had made their departure, with her tea service put away, Georgiana gave birth to a daughter at 3am.

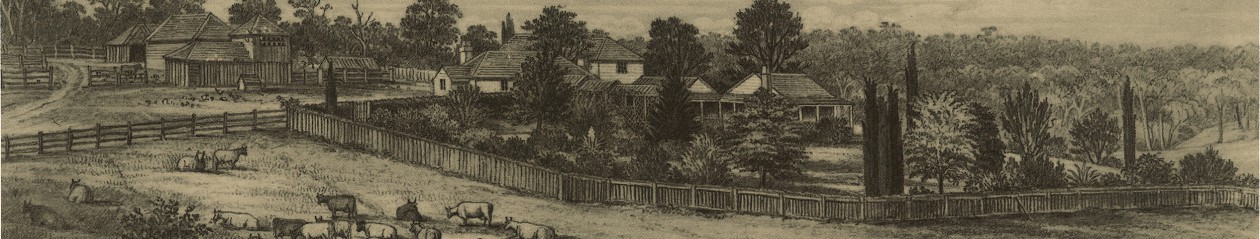

In Australian homesteads like the Wragge family properties, Yallambie and Tulla, there is little doubt that tea drinking would have been an established routine, enjoyed by both family and the staff. Tea was regarded as a staple for such households, “Large supplies of essentials, such as flour, sugar, and tea, were stored…” (Calder: Classing the Wool, p101) with black teas from India and Ceylon later in the Century replacing the Green China teas that had earlier been popular. Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management said that black tea was “more highly flavoured than the Chinese” calling it, “The most popular non-alcoholic beverage in this country, (Great Britain).”

Throughout the 19th Century and indeed for much of the 20th, to be an Australian meant also to be a part of the greater British diaspora. The Brits had for years been putting milk in their tea, a practice that is thought to have started in the 17th or 18th Centuries when the Chinese porcelain cups used to serve tea were feared to be so delicate that hot tea might crack them. Milk was added to cool the liquid and reduce the risk. Black tea is best brewed at hotter temperatures than green so with the industrial age came a more cynical reason for using milk. Employers added it to shorten the length of tea breaks since hot black tea required long tea breaks to drink it. The addition of milk cooled the tea thereby shortening the breaks required and increasing available work time for the factories along the way.

There was a time years ago when non-homogenized milk was delivered to houses in glass bottles topped with foil. The magpies would peck at the top to get at the cream if you left the bottles out late in the morning . In the Heidelberg area milk came from the Eaglemont Dairy and I’m guessing was probably delivered by a milkman called Ernie driving a very fast milk cart. Some stores are now selling non-homogenized milk again describing it as organic. The milk needs a shake before using but I like the resulting smoother, rich creamy flavour.

Tea drinking has always been a way of life in this house. My wife and I met over a cup of tea and like the British factory workers guzzling their lukewarm, milky tea while production stopped, any project around this house or in the garden for that matter needs to be interrupted regularly by a super-sized cup of tea in order to proceed smoothly.

For mine, the only way to make tea is for it to be properly brewed in a pot and not with the sweepings from the tea factory floor collected into little paper bags with a string attached. I know this preference is probably atypical today and that many people now might not even own a teapot. We on the other hand, while having many, always have room for one more. Last week we were visiting a large, well known Greensborough thrift emporium where we found a very nice EPNS pot which was purchased for $12. It was nearly black with tarnish but polished up very quickly when we brought it home. Inside was found a touching, hand written note describing it by a now lost and forgotten hand as “Nanna’s silver tea service teapot”. Apparently nobody had wanted Nanna’s best pot since it had been relegated to an Op shop. Well, we’ve given it a home and have been making tea in it all week. It pours beautifully and joins many such “heirlooms” which reminds us of the long line of tea soaks we have on both sides of the family.

Tea drinking isn’t complicated. Sip, taste and enjoy one of life’s little but unregarded luxuries. Arthur Phillip enjoyed it. The jolly swagman would have if given the chance. So for those coffee drinkers who don’t know how, or any who would otherwise prefer to use a paper bag with a string attached, here’s what to do.

Use freshly drawn water and fill the kettle only with the amount you need. Black tea is best made using water boiling at or near 100°C. Remember the old saying, “take the pot to the kettle, not the kettle to the pot.” This is so the water is still boiling when it hits the leaves. Use one teaspoon of tea leaves for each person, and add an extra one for the pot.

Allow the tea to stand, brewing the tea leaves from three to five minutes depending on the style of tea, plus your own individual taste.

Stir the pot when you are ready to pour. I use a spoon but my wife just turns the pot around on the table with a giddying regularity. Don’t use a knife if you are in any way superstitious. Remember the old saying, “Stir with a knife and stir up strife”. Use a strainer if you don’t like leaves in your cup but the fact is, we can drink huge amounts of leaves without harm. I had a friend whose grandmother was superstitious and liked to make a show sometimes of reading tea leaves at the end of a cup.

When taking milk in your tea, always add the milk to the cup first for a smoother flavour and to avoid scalding the milk. Choose your favourite tea cup and saucer, pour the tea slowly and take time to inhale and appreciate the aromas created by the fresh brew.

If the “white death” of sugar takes your fancy, then add a spoonful and stir but for mine, you will lose the taste of the tea by adding sugar to it.

So make mine white and without please. Hooroo, I’m off for a cuppa.