In an unmannerly modern world it seems that the epithet “gentleman” is more likely to be found these days on the door of a public loo than out there in the less than genteel mores of society. It might be that this is evidence of a new standard but the fact remains, it was not always so. The word “gentleman” at one time was a word that carried a certain polite social expectation since to be a “gentleman” removed a man, at least in his own mind, from the general hoi polloi of the professional and labouring classes, the “great unwashed” of literature.

In 1861, Yallambie’s Thomas Wragge signed the certificate of his marriage describing himself as a “gentleman of Lower Plenty” while his bride signed herself as Sarah Ann Hearn, a “lady”. A hundred years earlier, Lord Chesterfield had written plenty of advice about what this actually meant in practice, advice that had become pretty widely accepted by the time Wragge brought his bride to Yallambie, but it is advice which today has been largely forgotten. The good Lord is better remembered now chiefly for having a chair named after him.

As a code, the Chesterfield ideal flourished in the otherwise egalitarian society of the Australian colonies of the 19th century in spite of, or perhaps because of the 20 thousand kilometres by sea that separated Australian society from the rest of civilization. Transplanted from the British Isles by early settlers the code attempted to reproduce as far as possible the traditions of a polite society in a rude world under the demanding vicissitudes of an alien sun. Colonial intellectuals might look to the contents of a man’s library to judge a gentleman’s character, the dandies the cut of his coat and heralds the existence of armorial bearings, but for all of this one standard remained inviolable. That was the ability of a man to live respectably within his means on an unearned income.

When Thomas Wragge decided to take his growing family on a visit to England in 1892 to see the land of his birth, he did so as a representative of Australia’s new landed squattocracy. The family chose to travel that year as saloon passengers on a single class steamer, the Peninsular and Orient Steam Navigation Company’s SS Valetta with the manifest describing each member of Thomas’ family as either a “gentleman” or “lady”. Keeping up appearances, there would be no room for any of life’s riff raff on this voyage for Thomas.

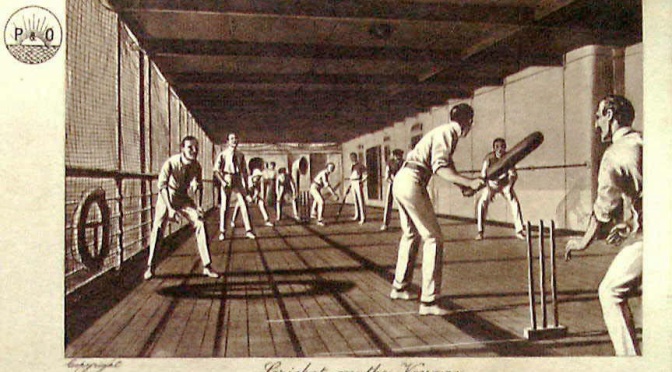

The ship left Melbourne on the 26 March, 1892 and stopped at the Port of Adelaide where ongoing passengers were excited to find Lord Sheffield’s 1891-92 returning English Test cricketers come on board. The team was captained by the renowned Dr William Gilbert Grace, a huge figure in the cricket of this era in both his sporting achievements and his commanding presence – 6 ft 2 in (1.88 m), an ever expanding girth and a bushy, black pirate beard to match. To the great interest of Thomas’ sons, nets were put up on the deck to allow the cricketers to keep in condition during the long sea voyage and to their general excitement Thomas’ youngest son Harry, then nearly 12 years old, was given the opportunity to bowl to the great W G in the nets. The unexpected result of this would be remembered by his family for generations with Harry’s nephew, Frank Wright later writing of the encounter and of Harry’s subsequent development as a cricketer.

“In the playing of deck games, young Harry, then aged only 11 or so, clean bowled Grace in a game of deck cricket. It seems to have created such an uproar that Grace lost his temper, so things could have been so-so for a while. The aura surrounding young Harry for this feat was probably the cause of his later interest in cricket. My first recollection of him in the early 1900s is in his flannels, eating an enormous meal at Yallambie one Saturday evening after having played in some match at Heidelberg.”

F S Wright, 1949, State Library of Victoria, Manuscript Collection and quoted by Calder, p119, Classing the Wool and Counting the Bales

The lack of grace of Grace at losing his wicket to an eleven year old might seem to have been a bit of an over-reaction but the bearded cricketer was well known for possessing a highly competitive streak. The stories of his refusal to “walk” when out are legendary and although some of them are probably apocryphal, one sometimes quoted tale recalls the cricketer coolly replacing the bails in a first class game after they had been dislodged by the leather, remarking as he did so for the umpire’s benefit, “Windy weather out here this morning.”

Such blatant examples at gamesmanship could have and sometimes did have unintended consequences in the sporting arena. In a match at The Oval in England in 1882, Australia’s Fred “The Demon” Spofforth is said to have boiled over in righteous anger at an unsporting run out by Grace of an Australian batsman who had wandered out of the crease to do a “bit of gardening” between balls. It inspired “The Demon” to a bowling rout of the Englishmen with the Australian quick capturing a decisive 14 wickets, Australia winning the match by seven runs with a famous published “obituary” to English Cricket afterwards appearing in the press, the body to be “cremated and the ashes taken to Australia”.

Such blatant examples at gamesmanship could have and sometimes did have unintended consequences in the sporting arena. In a match at The Oval in England in 1882, Australia’s Fred “The Demon” Spofforth is said to have boiled over in righteous anger at an unsporting run out by Grace of an Australian batsman who had wandered out of the crease to do a “bit of gardening” between balls. It inspired “The Demon” to a bowling rout of the Englishmen with the Australian quick capturing a decisive 14 wickets, Australia winning the match by seven runs with a famous published “obituary” to English Cricket afterwards appearing in the press, the body to be “cremated and the ashes taken to Australia”.

In a way strangely pertinent to our story, these “Ashes” as they became known enjoy a vague familial association with Yallambie which you won’t find mentioned in any of the many history books of the subject. Wragge’s wife, Sarah Ann Hearn was a full cousin of Sir William Clarke, 1st Baronet and it was at Clarke’s country seat, “Rupertswood” near Sunbury that the most enduring and famous trophy in cricket was created as a nod to the earlier death notice to English cricket. One of cousin Clarke’s many hats was as president of the Melbourne Cricket Club and he was instrumental in bringing the English cricketers to Australia in 1882 after their shock loss at the Oval.

The tour became known as the battle to reclaim the imaginary Ashes of newspaper obituary invention but how much Sarah Ann had to do with her cousin’s family at Sunbury in this era is uncertain. What is known is that her husband Thomas’ brother, Henry Wragge, a veterinarian was at Rupertswood around this time working in Sir William’s stables and that Henry had been living with his brother’s family at Yallambie. Perhaps the story of The Ashes had become a family anecdote to them by the time Harry had a chance to roll his arm over to Grace 10 years later. It’s a thought.

W G Grace remained a much loved cricketer for many years with the public both in England and abroad and a respected and sometimes feared opponent. The contemporary monthly almanac “Cricket” wrote of the 1891-92 English tour of the Australian colonies, “The great as well as the most pleasing feature of the tour to the general public was Dr W G Grace’s consistent success as a bat. Time has not even now withered, nor custom staled his infinite variety.”

It was the second tour of the Australian colonies for Grace, 18 years after the first and the first of the Test cricket era. W G was 43 years old at this time but still took third place on the English Test batting averages while in Australia.

Grace chose to take the field as a Gentleman/Amateur as opposed to the Player/Professional class but herein lies one of the great shams of what is sometimes referred to as the “Golden Age” of cricket. The game could be said to have been suffering from a sort of existential crisis at this time for to be a gentleman in cricket parlance meant to take the field purely for the love of the game and without financial incentive. At least that was the theory. “No gentleman ought to make a profit by his services in cricket,” wrote the MCC in November, 1878. Sounds simple enough doesn’t it but it was a decree in practice openly flouted by many of the greatest of the Amateur cricketers of the era. This was a time when leading Amateurs were often better rewarded than the game’s Professionals, commanding high appearance fees and extravagant expense accounts but still demanding separate gentlemen’s dressing rooms from their labouring class team mates. Grace was no exception and made a considerable sum of money as an Amateur in 1892 even while Lord Sheffield’s loss making tour racked up expenses, including the cost of the presentation of a magnificent silver shield to the colonies to be used for a domestic competition still bearing his name to the present day.

As an in demand if theoretical Amateur first class cricketer, Grace probably didn’t have a financial need to take his medical practice too seriously, which may have been just as well for his patients as I’m thinking the cut of his scalpel might not have matched the cut shot of his cricket. On one occasion in 1870 while playing for the MCC, Grace then a 22 year old medical student was present when an opposing batsman was struck in the head by a rising delivery on a difficult wicket. Grace took command of the situation and prescribed a stiff brandy for the patient and a lie down who, without further treatment, was dead four days later from an undiagnosed fractured skull.

So much for medicine as a profession for one of the great Amateurs of the game.

It’s natural to think of sport as being a form of play but for the Professional there is no doubt that it has become a task orientated occupation like any other involving physical exertion and carrying a formal structure. In other words, work. Play on the other hand, is all about leisure and having a good time and it is perhaps this distinction that has always separated the Amateur from the Professional and the Gentleman from the Player.

The reality of this has become clouded over the years but any park cricketer today could probably tell you more about what it means to play the game in the amateur spirit than those who have played the game as Amateurs historically. There have always been cricketers who have pulled on the flannels for nothing more than the smell of the new mown grass, the blue skies and the sheer love of the game, including this writer in his youth as an indifferent but always hopeful opening bat for the Lower Eltham CC.

Modern associations with the game of cricket are rarely found in Yallambie but they do exist if you look carefully. The only full sized cricket grounds in Yallambie are those that can be found inside the Simpson Barracks but I’m not about to enlist to get a game there. A junior team was founded locally in 1979 and fielded sides, the Yallambie Sparrows and the Yallambie Eagles across two decades in the NDCA, JIKA, PDCA and HDCA using the Winsor Reserve in Macleod as their home base and winning premierships in 1983, 84 and 86. Alan Connolly who represented Australia as a medium-fast bowler in Test cricket from 1963 until 1971 lived in Tarcoola Drive, Yallambie after retiring from first class cricket. Probably the most unique cricket connection in Yallambie however is the existence of a book shop in a suburban court side home location dedicated entirely to the subject of cricket. Roger Page Cricket Books has operated in Yallambie for 50 years with a customer base from across the world.

The days of thinking about cricket in terms of Amateurs and Professionals are long gone, if they ever truly existed with the last of the prestigious “Gentlemen versus Players” games staged in 1962 after which the MCC voted to abolish the concept of amateurism altogether. Next month will mark the start of a new Ashes campaign, the 71st in the history of the game and if there’s still room to remember the principles of that earlier era I’m afraid you won’t find them voicing it on Rupert’s Fox Sports. The introduction of a numbering system this year on the backs of cricketers’ whites marks one more break from tradition but what can we expect in a world where players take the field with huge pay packets in the pockets and a win at all cost mentality that saw three Australian Test players shamed and banned last year for ball tampering. The boos the English crowds reserved for the players on their return to first class cricket in the recently completed World Cup “coloured pyjama” short form of the game was not unexpected. Just a bit ironic. Theirs was not the first occasion of cheating in cricket and it won’t be the last. Just the most amateurish.

It may be true that the only Gentlemen to be found in cricket today is in the form of a word on a dressing room door, but watch out. Come the first ball bowled in The Ashes at Edgbaston on the first day of August, expect to see batsmen doing what they have always done in cricket in every form of the game. Flashing the outside edge of a bat at a rising delivery and as we say in this country, “Swinging like a dunny door”.