“He persuaded a man from Geelong to pose as a buyer, and that man finally made a deal with Mrs Beaton, paid a deposit and obtained a receipt which he handed to Thomas. It has been suggested that Thomas promptly rode over to the pub, ordered everyone out of it and burnt down the building.”(Calder: Classing the Wool – recounting Thomas Wragge’s solution to Beaton’s sly grog trading at Tulla)

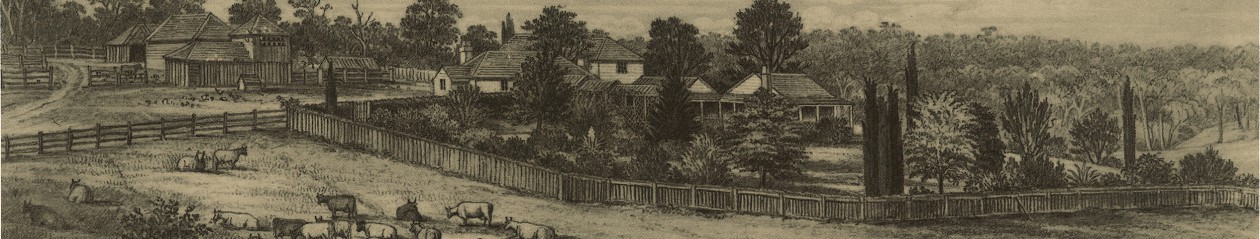

There are plenty of pubs in Australia but only so many matches in a box. While burning down the local might be one way of getting your men back to work, in the settled districts there are just too many pubs to make this practical. Along with the previously recounted story of the Plenty Bridge Hotel in Lower Plenty, in Thomas’ day there was no shortage of drinking places in the Yallambie area, with multiple hotels located at Greensborough and Heidelberg and country style public houses located at other places.

Thomas couldn’t burn them all down. Well, could he?

Wragge wasn’t the first nor was he the last to attempt to impose some sort of limit on the availability of intoxicating liquor in Australian society. The ups and downs of this story date back to the start of white settlement and Governor Phillip’s laudable if futile attempts to put a ban on the hard stuff. It was a ban that was fraught with impossible difficulties for as Robert Hughes explains in his popular history of Australia, “The Fatal Shore”:

“Colonial Sydney was a drunken society, from top to bottom. Men and women drank with a desperate, addicted, quarrelsome single-mindedness.”

Banished to the other end of the world and torn from everything and everyone that was near and dear to them, rum was their drink of choice, which was handy since it was also the chief form of monetary currency. Coin had developed an annoying habit of leaving the colony with traders just as soon as it could be imported, a problem not rectified until they started punching the middle out of Spanish dollars. A barter system was what was needed and that’s where rum came in. You could drink yourself into the poor house, or an early grave. Quite often both. The First Fleet convict and skilled blacksmith, William Frazer was one who insisted on payments only in rum and not surprisingly it wasn’t long before he was dead after going out on one too many benders. It spoke volumes about colonial society that a man could drink himself to death at the same time so many lived on the very brink of starvation.

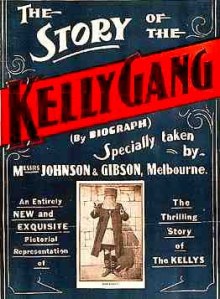

The New South Wales Corp, the infamous “Rum Corps” of history, saw an opportunity and in defiance of East India Company trading rights, set about cornering a monopoly in rum, enriching themselves in the process in ways more akin to the later gangsters of Prohibition era America than the officers and enlisted men of a regiment in the British Army. The coup d’état that ousted New South Wales fourth governor, William Bligh in 1808, was sparked initially by the attempted arrest of the former Rum Corps captain, John Macarthur who had attempted to import an illegal still. Successive governors had previously attempted a total ban on the distillation of spirituous liquor in the colony, but the publication under the very nose of authority of a how-to guide for making bootlegged brandy in the fourth issue of the colony’s first newspaper, the 1803 Sydney Gazette is a good indication of just where they were going on this.

The soldiers involved in removing Bligh and installing his deputy, Major George Johnston would never have owned up that they were engaged in a Rum Rebellion when they allegedly pulled Bligh out from under the bed where he had been hiding. They would have told you they were engaged in a fight for freedom, which was a bit rich given that they were living in a convict colony and that they were the jailers. In essence, the rebellion was an attempt to maintain the soldiers’ happy go lucky trading monopoly and it wasn’t until 50 years later when William Howitt called it a “Rum Rebellion” in “Land Labour and Gold”, a book in which we remember he also described his visit to the Bakewells’ Yallambee Park, that the term really caught on.

This trade in hard liquor may have been seen by the early chroniclers as a sign of a sort of moral failure of the colony, but the on again, off again nature of the business did not preclude a number of legally appointed legitimate attempts to start a home grown wine and ale industry. As early as 1802, Governor King received a letter from the Secretary for the Colonies Lord Hobart, applauding him for his efforts to stamp out the improper importation of spirits into Sydney while suggesting instead that, “The introduction of beer into general use would certainly tend in a great degree to lessen the consumption of spirituous liquors.”

The First Fleet convict, James Squire had begun brewing something which it’s said vaguely resembled beer soon after arriving and continued to do so in the years following, with and without official sanction. It’s alleged that without hops to flavour his first attempts, James resorted to using horehound herb stolen from the First Fleet medical stores as a sort of substitute, getting away with the crime because the court judges liked a drink. Or so it was said. Eventually Squire managed to establish himself as brewer of possibly local distinction and certainly of considerable wealth, although an epitaph of one of the regulars at Squire’s Malting Shovel Tavern recorded in a cemetery at Parramatta in the early days, perhaps suggests something about the quality of the colonial product:

“Ye who wish to lie here, drink Squire’s beer.”

Beer drinking was actually seen to be a healthy alternative to drinking water at a time when local water was so often contaminated by pollutants and disease, the fermentation process rendering the water safe. By the time of settlement in the Port Phillip District from the mid-1830s, colonial brewing practices had become pretty well established. James Graham, the Bourke Street merchant and second owner of Banyule Homestead in Melbourne, records in his letters instances where local beers were preferred over the imported products, the colonial beer being not only cheaper but more readily accessible.

But it was Howitt who described the goldfields and recorded his observations of the mine workings where the passage of the diggers was recorded not only by the holes made in the landscape but by the piles of empty bottles left behind. Later, in the pastoral era at a place called Innamincka, on Cooper Creek in South Australia, a famous bottle dump grew to be over 200m long and 2m high. The pile of empties was mainly empty rum bottles. To the surprise of no one, there were no Tarax or Fanta bottles. The man-made glass mountain at Innamincka stood for years like a gleaming beacon, long after the place itself had become a virtual ghost town, glistening in the sunlight with a sparkle that could be seen from miles away like a monument to the unquenchable outback thirst.

The 1830s was the decade that saw the founding of the Temperance Movement in Britain, a movement that advocated a complete abstinence from alcoholic drink. The idea when it arrived in Australia eventually resulted in the creation of coffee palaces which were seen as an alternative to public houses. At 400 rooms, one of the largest of these was the Grand Coffee Palace in Melbourne, (now the Windsor Hotel) which famously and ceremoniously burnt its liquor licence when opened in 1886. It was a show of principle but a show not necessarily rooted in business reality. The liquor licence was returned when it had to be admitted by all concerned that plenty of surreptitious drinking of alcohol was actually taking place at the establishment. The Coffee Palace was fighting a losing battle.

Dead blacksmiths and army insurrections aside, it seems that there’s always been a want for this stuff. Show me a one horse town these days where the pub has closed down and I’ll show you a town teetering on the edge of extinction. Even the Yallambie General Store is selling booze now, in its new role as an off licence trader. That store happens to be located opposite our kindergarten, which seems to me to be some sort of a contradiction but then this wouldn’t be the first. Years ago I had a part time job at a licenced grocer in Rosanna from where we would go out in the grocers’ van delivering orders. One regular customer I recall was a trip to the Sisters of Mercy Convent in Rosanna Rd. We left a weekly supply of a dozen bottles of Fosters there, religiously. The nuns used to say that the bottles were for the workman in his garden out back, but I wonder?

Armed with his box of matches 150 years ago, Thomas Wragge didn’t burn a liquor licence, but a look at a page from a Yallambee day book of the 1860s at a time when Wragge was subleasing the property shows another possibility. In those pages is recorded a surprising detail of a trade in whisky, brandy, ale and aged sherry. Barrels and barrels of the stuff. Maybe Wragge would have told you the sherry was for the cook?

Temperance in its original meaning signifies a moderation of action, thought or feeling and it was only later that it became generally associated with its other meaning, the meaning with the capital T. With a well-stocked cellar and an established tradition of wine making already in place at Yallambie, Thomas Wragge, like many a nun and Colonial Governor before him, and kindergarten teacher after, had arrived at the consensus.

All things in moderation.