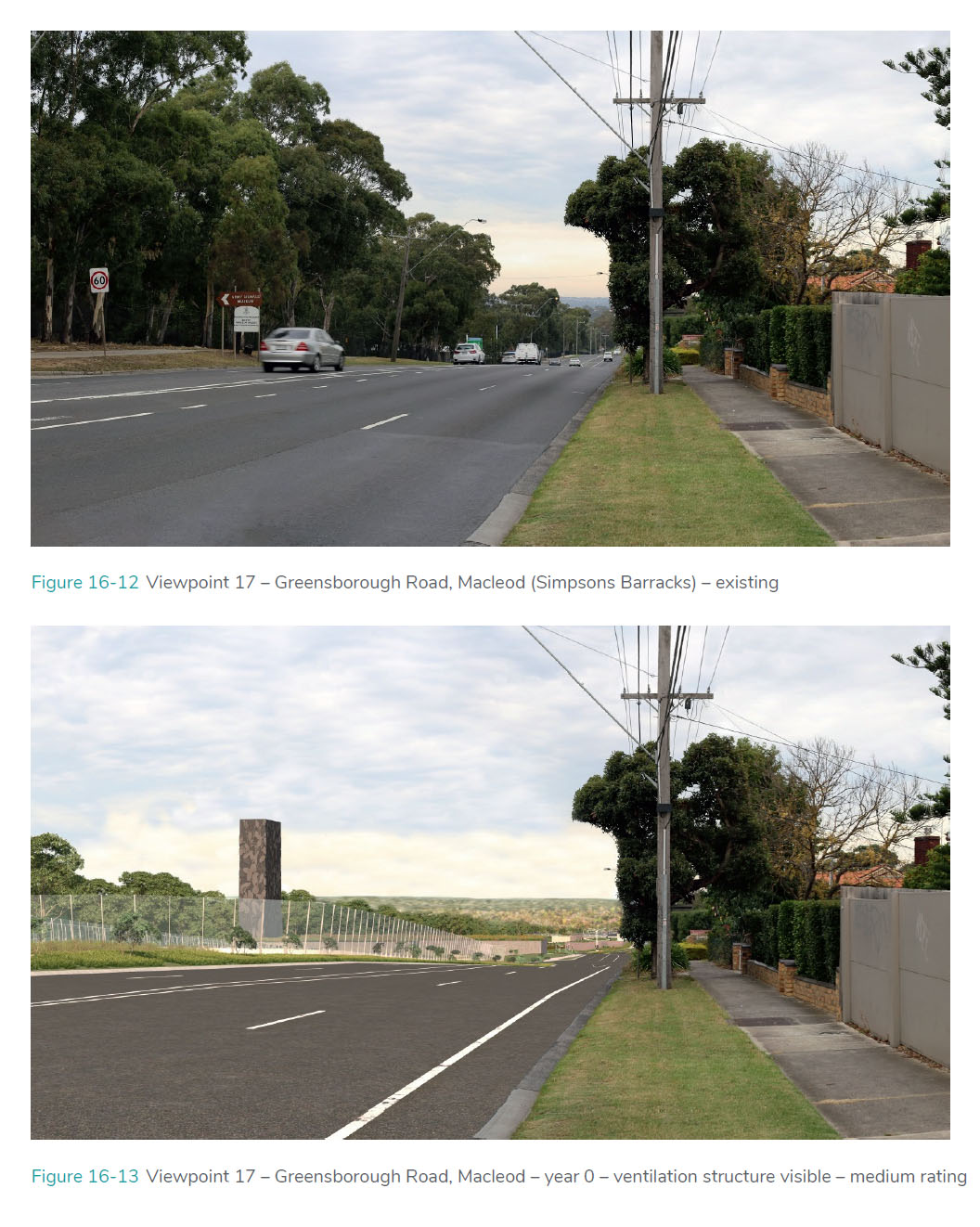

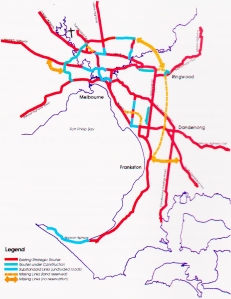

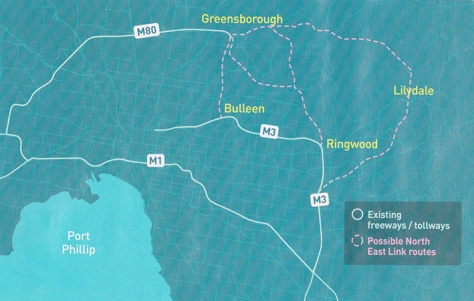

You’ve got to feel something for the persecution poor old William Posters has suffered from the Old Bill. He’s been copping it from the coppers for years, the words “Bill Posters Prosecuted” once upon a time a familiar sight on awnings and placards across the city. You can still see a bit of this, usually on building sites, but the lack of any meaningful bill posting lately along those miles and miles of hoardings hiding the ugly hole in the ground that is the start of the North East Link, has me thinking. If the sight of paper posters peeling in public places isn’t a thing in these days of the internet and social media – then what has replaced it?

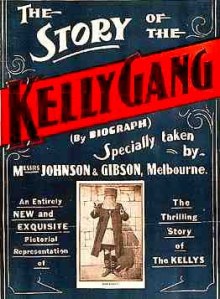

Once upon a time, billposting was a pretty common sight all over our fair town. Billposting billposters battled with each other to cover every available vertical surface, jousting with long paste brushes on muddy Melbourne streets like knights on the Field of the Cloth of Gold. In the eyes of these bill posters, any wall surface that wouldn’t hold a poster was simply a waste of space. The posting of bills was used to promote anything and everything. From cure-alls to boot blacking and election candidates to circus clowns. Sometimes, it was hard to tell the difference.

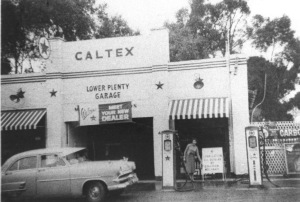

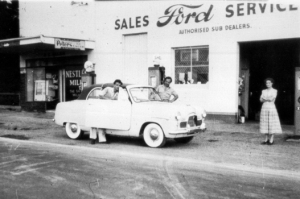

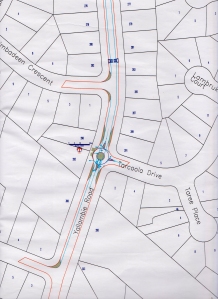

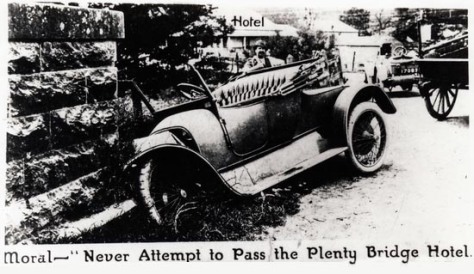

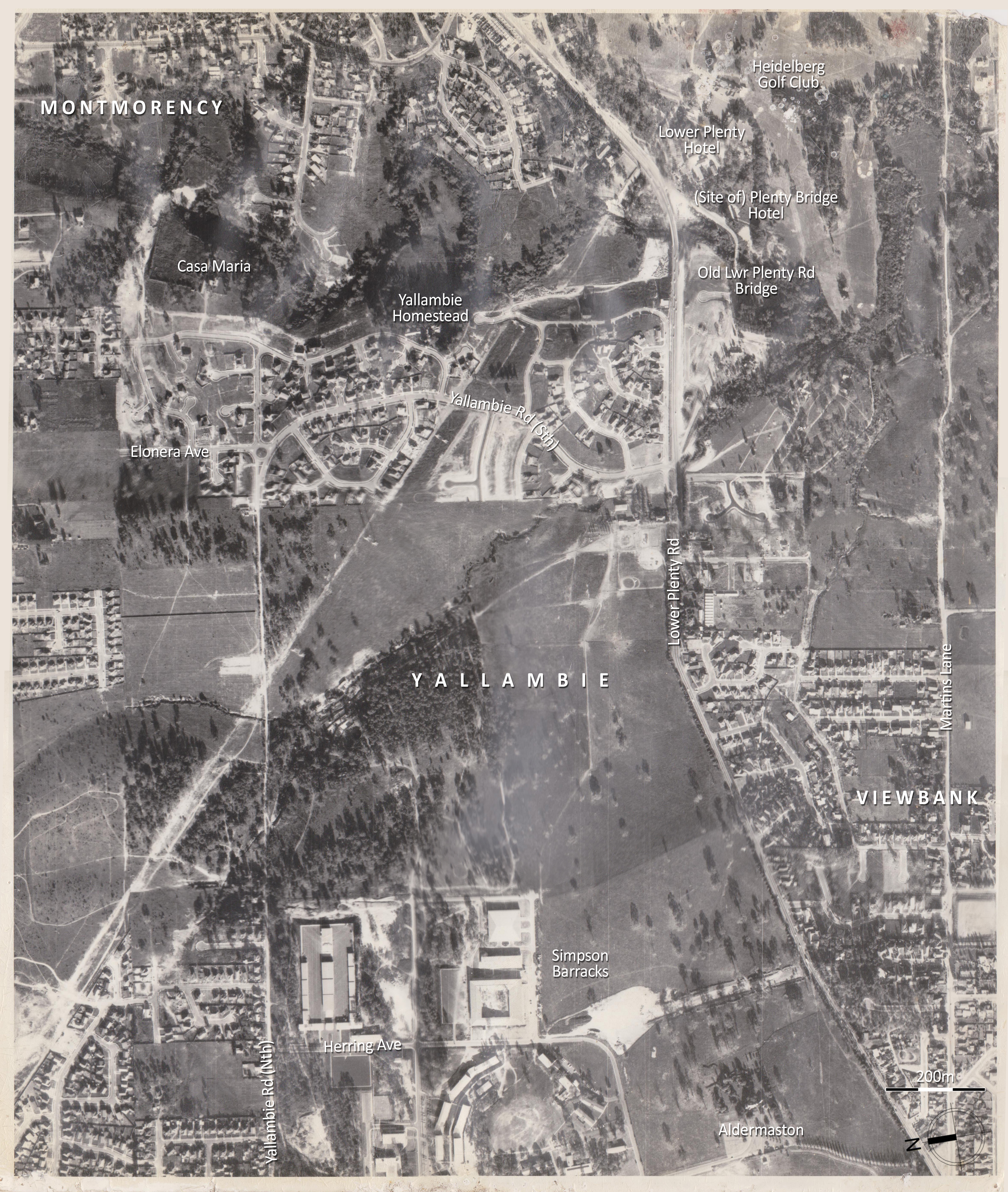

Even out here at the Plenty Bridge, in what were the early years of the motor age at a time when Yallambie and the surrounding district was still considered to be, “a bit out in the country”, a large billboard was put up at the turn of the old road where it crossed over the River. At Heidelberg, along the post and rail fencing that lined the upper reaches of Burgundy Street, advertisers dispensed with the idea of billboards altogether and simply scrawled their messages onto the fence railing itself.

The process of writing messages onto public spaces was nothing new. The expression “graffiti” is derived from an ancient Greek word which means “to write”, so it is something that been around a long time. In fact, humans have been making marks on walls since a time before there were humans. Some prehistoric cave art has been attributed to our vanished Neanderthal cousins, although what they could possibly have been recording back then must forever remain a mystery. I’m guessing something like, “Zog has bad teeth”, “the Mammoth Boys can go suck dinosaur eggs” or the inevitable “Loana is hot” – which must have been an especially important thing to note back in the Ice Ages. Although these marks may be a form of ancient graffiti, to the modern observer they are something else – something we now call cave art.

Proper cave art may have had a religious significance to the caveman, but by historical times the idea of scribbling on walls was everywhere. Any fan of history will remember the bawdy graffiti of Pompeii and Herculaneum, and any fan of Monty Python will remember Brian painting “Romans go home” in 10-foot-high letters of appalling Latin grammar onto the walls of Herod’s palace. Here in 19th Century Victoria, early tourists left their own small marks on the Sisters’ Rocks outside Stawell, but these days those marks have spread like a contagion into London double decker bus sized lettering, splashed all about in lurid colours. The Northern Grampians Shire council has said it has no plans to remove the graffiti at the Sisters’, instead noting its tourism potential, but here’s the point.

The thing about graffiti is that it tends to attract more of the same, and more so the longer it goes without removal. I can almost tell you when this started in Melbourne properly. When I was a kid, there was an American situation comedy television series set in New York. It arrived on Australian TV screens soon after people started installing colour reception into their homes, the opening titles showing New York subway trains painted in lurid graffiti. I remember the boys at school discussing the show, not because of its dubious comedy potential but because of that scene in the credits depicting trains travelling about in Brooklyn. “Did you see those painted trains? Nobody ever cleans them.” Soon after this we started seeing Melbourne’s trains painted in similar style and for a long while, nobody seemed to clean them either.

By the early 2000s graffiti, especially around Melbourne’s newly privatised public transport system, had become an epidemic. Graffiti artists routinely held onto the back of moving trains to spray paint the carriages turning them into moving billboards, always keeping one step ahead of the authorities who regarded this as commonplace vandalism.

These days Melbourne’s trains are kept more or less graffiti free but take a step down any inner-city street or past a railway easment and you’ll see that as a form of artistic expression within the systems of the broader structures of the city, it is an art medium that hasn’t gone away. In some places like Smith Street, Collingwood the authorities seem to have given up altogether trying to keep graffiti under any sort of control. The result is that a fine Victorian streetscape has been ruined by a scrawl of stupid spray-painted tagging, randomly splashed without any thought across every available surface and without any pretence that what we are seeing could be considered a form of artistic expression. In other places like Hosier Lane in Melbourne however, the work of graffiti artists is actively encouraged, even supported, and deserves the other name that many people give it – street art. Tourists come from near and far to see an artform that in this situation has entered the cultural mainstream. Art as they say, is in the eye of the beholder.

Street art is by it’s nature an ephemeral media, created in a public space and more often than not, without official permission. While a Banksy mural can be praised, prised off the wall and sold to a gallery for millions, other street art goes either unnoticed, is painted over or left to weather in the elements. All the same, no matter how appealing individual street art might be, it seems to me that there’s always going to be some knuckle head who will come along later and scrawl a “tag” across it.

At the Yallambie milk bar and general store, the side wall facing the electrical easement has for a long time carried a rather cute painting of a kitten. I couldn’t tell you when this graffiti in particular went up, but it does carry the moniker “Meow” which it seems was once a well-known name on the Melbourne graffiti scene. It’s a bit faded now but the fact that it’s there at all has meant other, less creative tagging has inevitably followed Meow.

The separation between art and vandalism remains a subject largely still open to debate, but in some instances there has never been room for an argument. Late last year a red swastika appeared on a Council owned, Yallambie footpath. The symbol is of course an offence to display under the laws of this state, and offensive under the thinking of any right-minded individual. The police soon ensured its removal, but the question remains, just how many police resources should we devote to getting down on graffiti and when? Last week The Age newspaper carried a story under a headline “the crew that took police 20 years to crack” which told the tale of a 20-year-old fight to bring one member of a train painting graffiti gang of the early 2000s, the 70K gang, to justice. This particular graffiti artist had been living abroad for decades, beyond the reach of the long arm of the law. When he finally returned to Australia in order to visit a sick family member, he found the Old Bill waiting at the airport to greet him.

Police said that Scott-Howarth and the 70K crew were prolific vandals between 2001 and 2005. Scott-Howarth took massive risks to paint prominent infrastructure – trains and other public property – alongside fellow crew members ‘‘ Bonez’’ , ‘‘ Bald’’ , ‘‘ Karl’’ , ‘‘ Renks’ ’ and ‘‘ Meow’’ , whose work endures throughout Melbourne decades later. (The Age, 24 May, 2024)

The debate over what constitutes graffiti art and what constitutes graffiti vandalism will go on, especially since inside every one of us there’s an art critic just wanting to have a say. “I don’t know what art is, but I know what I like.” How often have we heard this? “Bill Posters” might be forgotten, his place now occupied by this thing they call graffiti art, but think again if you expect the Old Bill to be a sympathetic exhibition critic.

Graffiti artists and graffiti vandals will continue doing what they do, and the police will continue to chase them, which is what they do. Perhaps it’s the very illegality that makes this sort of thing a proper artform in the eyes of so many people. It’s an artform that these days is demanding of recognition, but when it gets that recognition, will it still be art?

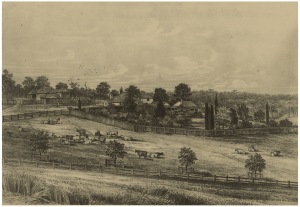

![2. "Dr. Godfrey Howitt's garden" [sic]", SLV.](https://yallambie.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/howitt_slv2.jpg?w=258)