If I owned a bucket filled with all things that I had wanted to do in one life, I think I’d turn it upside down right now and have a good long look for the hole I’m sure must be down there somewhere. It’s true the bucket list of all we mean to get done never quite measures up to our expectations, something the Spanish call, “mañana, mañana” but I’m wondering if what I have is really less of a bucket, and more a colander sieve.

When I think about it, there are things I’ve done, some I’ve tried, and others I never managed and thankfully never will now.

For example, I never learned to play the bagpipes, nor climbed to the Third Step of Everest or represented my country in breakdancing at an Olympic sport. The reality is I’m running out of time to do some of those things, but looking past that list now, there’s one thing I never did. While I’ve warmed my hands in front of plenty of smoky parlour room fires in my day, that’s about as far as it went. The truth is, I have never, ever wanted to wake up coughing in the morning with smoke curling out of my nostrils like Bilbo’s dragon in the book.

You see, back in the day when the boys at school were meeting out the back of the shelter sheds to talk about girls and to light up their fags, I guess I was just too darn busy building my model aeroplanes. Indeed, if I was to add up all the puffs on a cigarette I have tried in one lifetime, the total now must surely add up to less than the sum of one complete stick.

It might not be such a fashion these days, but not so long ago, nearly a half of all adult Australian men and a third of women smoked, a figure now supposedly reduced to about one in ten overall. We like to think this reduction is due to a better understanding of the dangers to health from smoking, but in fact these dangers were apparent almost from the very beginning. Tobacco had hardly arrived in Europe from the Americas when King James I wrote an anti-smoking diatribe, his 1604 “Counterblaste to Tobacco” where he expressed his distaste for tobacco, warned of its medical risks and compared the smoke to the pits of Hell.

“(a) custome lothsome to the eye, hatefull to the Nose, harmefull to the braine, dangerous to the Lungs, and in the blacke stinking fume thereof, neerest resembling the horrible Stigian smoke of the pit that is bottomelesse.”

Although James placed a heavy tariff on tobacco imports, it made little difference to whether people smoked or not. Tobacco use is highly addictive and demand for the product grew exponentially. By the 19th Century, smoking could be found in almost every walk of life. Smokers smoked tobacco either in pipes made of clay, briar wood, or for the toffs, in the shape of cigars. Cigarettes on the other hand were rare, being thought of either as effete, or even worse, foreign.

Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha was foreign but like a good Englishman in his adoptive country, he smoked a pipe, somewhat to the annoyance of his wife Queen Victoria who hated tobacco in all its forms.

At one of Victoria and Albert’s favourite homes, Osborne House on the Isle of Wight, above the doorway of every room entrance, the letters V and A are entwined into a monogram. Above every entrance that is, bar one. The exception was the door to the smoking room where a solitary “A” stands, proof positive of whose realm this was.

The concept of a room dedicated to smoking activities developed throughout the Victorian era. Primarily thought of as a masculine activity, tobacco use could be confined within the room, a place where men could escape the conventions of the surrounding household. It was a retreat few women and no children entered, a place where the reek of tobacco smoke in carpets and heavy curtains could be limited inside a closely confined and mysterious, male domain.

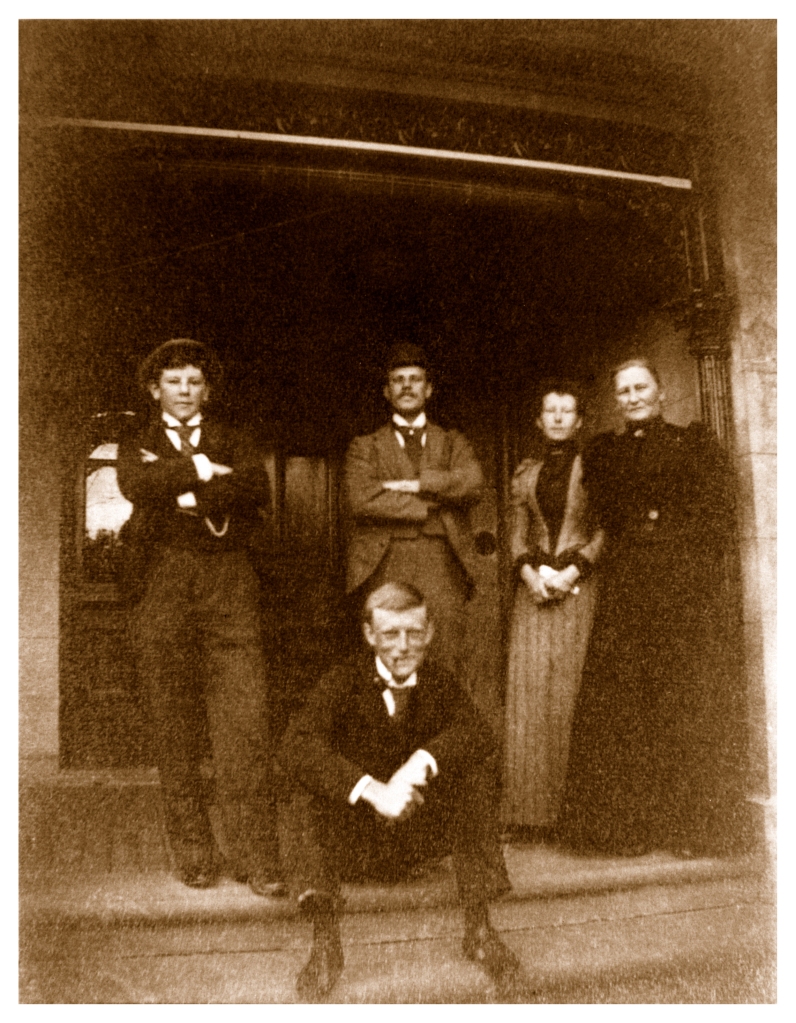

Rooms given over to the finer “art” of smoking became the fashion and at Yallambie, provisions were made for a room dedicated to the pursuit. It was a place where the Wragge men could smoke in comfort without interfering with the running of the rest of the household.

“The smoking-room, beside and east of the drawing room… had two southern windows overlooking the garden, and it had a third, giving onto the eastern verandah and overlooking the river valley. Essentially it was an evening room to which the men could retire after dinner to smoke and discuss affairs that interested them.” (Calder: Classing the Wool and Counting the Bales, p82)

In 1864, Robert Kerr had written in his influential book, “The Gentleman’s House” that, “The

pitiable resources to which some gentlemen are driven, even in their own houses, in order to be able to enjoy the pestiferous luxury of a cigar, have given rise to the occasional introduction of an apartment specially dedicated to the use of Tobacco.” Kerr suggested that a smoking room should be positioned to face west, apparently with the intention of observing cigar smoke curling up through the subtle half-light of evening, but at Yallambie the smoking room faced east. Maybe Wragge hadn’t read Kerr’s book, or more probably, it was an arrangement that favoured the warmer Australian climate where the cool light of evening was to be preferred at the end of the day.

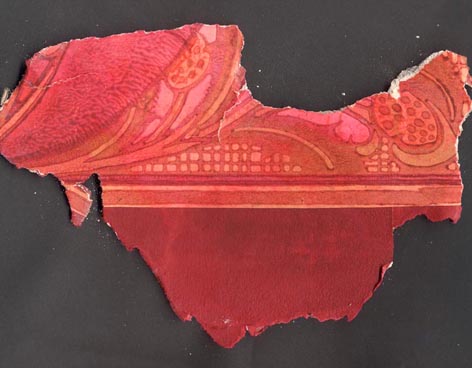

The Melbourne importing business, W H Rocke advised in a booklet of contemporary style in 1874 that a smoking room should, “give the chamber an easy and somewhat luxurious air, coupled with a tone denoting that it is not devoted to the purposes of the softer sex.” Although the Yallambie smoking room would later be absorbed into the larger space of the drawing room, surviving samples of a rather lurid wallpaper design from under the floor in this area show just how far this colour scheme might be pushed.

Perhaps not something you might have expected to find in Thomas Wragge’s strait-laced Anglican household. More akin to something from a French bordello. Maybe there was another side to the old boy not mentioned by the history books.

Imagine a whole room done like this.

The list for probate made in 1910 at the time of Thomas Wragge’s death catalogues the furnishings from this room: hearth rug and carpets, velvet and Nottingham lace curtains, a walnut veneer oval table and table cover, an American armchair and cane lounge, plus a Cedar sideboard and cottage piano.

With the wider availability of cigarettes that came with Bonsack’s machine making technology at the end of the 19th Century, pipe smoking and the need for purpose-built smoking rooms in the home faded. In 1911, B F and H P Fletcher wrote in their book, “The English Home”, that “some people do not object to smoking in any part of the house.” Indeed, instead of dedicated smoking rooms, homes were by this time more likely to have designated non-smoking rooms.

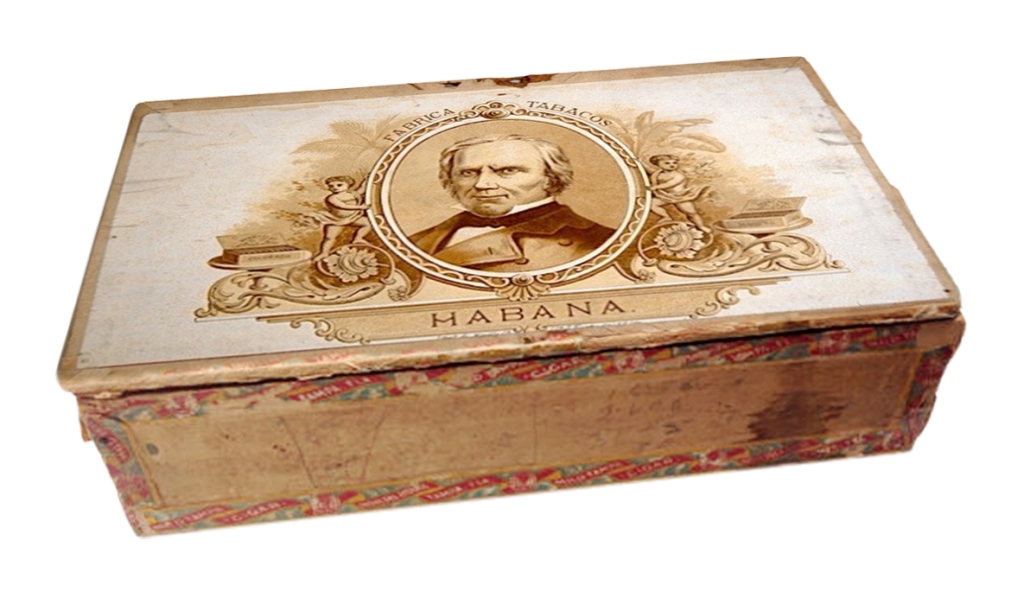

At Yallambie, the drawing room was extended during Annie Murdoch’s 1923 renovations by removing the adjoining smoking-room wall, creating a larger space that would be used regularly from that time as a “music room”. Certainly, people were still smoking at Yallambie, but they could now do this outdoors or elsewhere with readily available cigarettes. Cigars apparently were put away altogether, becoming a sort of luxury to be brought out only on occasion. Winty Calder tells in “Classing the Wool”, of one such occasion, a dinner party at Yallambie after the Second War which had been intended to impress a government minister:

“About 1954, the Federal Government put Nancy under considerable pressure to sell her property for extension of the Watsonia Military Camp. She opposed the resumption, but invited Mr Francis, Minister for the Army, to visit her at Yallambie. The entertainment she provided included good food and a Henry Clay cigar, out of which a silverfish popped. Whether for that or for some other reason, the government dropped its plans to compulsorily acquire Yallambie.”

(Classing the Wool and Counting the Bales, Winty Calder, Jimaringle Press, 1996).

You might say the attempted sale was close, but no cigar.

When I was a kid, I remember watching my Uncle Harry pottering about in his workshop at the back of his home in Alphington on our family visits. Uncle Harry never had a smoking room of course, but he did have an early sort of man cave where he busied himself with his hobbies. These were intriguing carpentry projects like the case for a grandmother sized clock, a wood turned lamp base, model boats and side boards and cabinets to house them in. My sister and I would watch him with curiosity, fascinated as the ash on the end of his other hobby, his roll your own cigarettes, grew longer with every passing minute while he worked. We took bets at how long this cigarette ash would be before it eventually dropped but as if by magic, it never did, at least not while we were looking.

Uncle Harry must have been gone these good many years, a face from a half-remembered childhood. I don’t know when he went or how, but given what we accept about smoking now, I can hazard a guess. The dangers from the tobacco industry are well understood now and probably they always were – yet tobacco industry products remain the biggest cause of preventable death in the world in the 21st Century, killing about 8 million people world-wide annually.

King James attempts to tax tobacco into oblivion 400 years ago ended in failure of course. 20 years after writing his “Counterblaste to Tobacco”, the King instead settled on a Royal monopoly of the hated product so that he could directly profit from the users.

So, what has changed in the last four centuries?

Not much, maybe. Governments still attempt to control tobacco use with prohibitive taxes, but I’m not sure that this is necessarily the whole story. Officially tobacco use in Australia has declined dramatically but illegal “chop chop” tobacco and vapes aren’t counted in any of these surveys. These products avoid the government bottom line, resulting in a situation the popular press has likened to Prohibition era America under the 18th Amendment a century ago.

The days of smoking as a sort of a masculine hobby confined within a dedicated domain inside the home and furnished by purpose made smoking paraphernalia are long gone. As a rather maligned minority activity with clear consequences to public health, you won’t see it as something added alongside breakdancing onto any of the bucket lists people make.

Sadly, most of those buckets were kicked by the smokers themselves, a long time ago.